TOP

Friday, December 16, 2011

Saturday, December 10, 2011

Apple - iOS 5 - See new features included in iOS 5.

Notification Center

All your alerts. All in one place.

You get all kinds of notifications on your iOS device: new email, texts, friend requests, and more. With Notification Center, you can keep track of them all in one convenient location. Just swipe down from the top of any screen to enter Notification Center. Choose which notifications you want to see. Even see a stock ticker and the current weather. New notifications appear briefly at the top of your screen, without interrupting what you’re doing. And the Lock screen displays notifications so you can act on them with just a swipe. Notification Center is the best way to stay on top of your life’s breaking news.

Newsstand

A custom newsstand for all your subscriptions.

Read all about it. All in one place. iOS 5 organizes your magazine and newspaper app subscriptions in Newsstand: a folder that lets you access your favorite publications quickly and easily. There’s also a new place on the App Store just for newspaper and magazine subscriptions. And you can get to it straight from Newsstand. New purchases go directly to your Newsstand folder. Then, as new issues become available, Newsstand automatically updates them in the background — complete with the latest covers. It’s kind of like having the paper delivered to your front door. Only better.

Reminders

A better way to do to-dos.

Next time you think to yourself, “Don’t forget to...,” just pull out your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch and jot it down. Reminders lets you organize your life in to-do lists — complete with due dates and locations. Say you need to remember to pick up milk during your next grocery trip. Since Reminders can be location based, you’ll get an alert as soon as you pull into the supermarket parking lot. Reminders also works with iCal, Outlook, and iCloud, so changes you make update automatically on all your devices and calendars.

Twitter

Integrated right into iOS 5.

iOS 5 makes it even easier to tweet from your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch. Sign in once in Settings, and suddenly you can tweet directly from Safari, Photos, Camera, YouTube, or Maps. Want to mention or @reply to a friend? Contacts applies your friends’ Twitter usernames and profile pictures. So you can start typing a name and iOS 5 does the rest. You can even add a location to any tweet, no matter which app you’re tweeting from.

Camera

Capture the moment at a moment’s notice.

Since your iPhone is always with you, it’s often the best way to capture those unexpected moments. That’s why you’ll love the new camera features in iOS 5. You can open the Camera app right from the Lock screen. Use grid lines, pinch-to-zoom gestures, and single-tap focus and exposure locks to compose a picture on the fly. Then press the volume-up button to snap your photo in the nick of time. If you have Photo Stream enabled in iCloud, your photos automatically download to all your other devices.

Photos

Enhanced photo enhancements.

Turn your snapshots into frame-worthy photos in just a few taps. Crop, rotate, enhance, and remove red-eye without leaving the Photos app. Even organize your photos in albums — right on your device. With iCloud, you can push new photos to all your iOS devices. So if you’re taking photos on your iPhone, iCloud automatically sends copies to your iPad, where you can quickly touch them up before showing them off.

Safari

Even better site-seeing.

iOS 5 brings even more web-browsing features to iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch. Safari Reader displays web articles sans ads or clutter so you can read without distractions. Reading List lets you save interesting articles to peruse later, while iCloud keeps your list updated across all your devices. On iPad, tabbed browsing helps you keep track of multiple web pages and switch between them with ease. And iOS 5 improves Safari performance on all your iOS devices.

PC Free

Independence for all iOS devices.

With iOS 5, you no longer need a computer to own an iPad, iPhone, or iPod touch. Activate and set up your device wirelessly, right out of the box. Download free iOS software updates directly on your device. Do more with your apps — like editing your photos or adding new email folders — on your device, without the need for a Mac or PC. And back up and restore your device automatically using iCloud.

Mail

Your inbox is about to receive some great new features. Format text using bold, italic, or underlined fonts. Create indents in the text of your message. Drag to rearrange names in address fields. Flag important messages. Even add and delete mailbox folders on the fly. If you’re looking for a specific email, you can now search in the body of messages. And with iCloud, you get a free email account that stays up to date on all your devices.

Wi-Fi Sync

Wirelessly sync your iOS device to your Mac or PC over a shared Wi-Fi connection. Every time you connect your iOS device to a power source (say, overnight for charging), it automatically syncs and backs up any new content to iTunes. So you always have your movies, TV shows, home videos, and photo albums everywhere you want them.

Samsung I9100 Galaxy S II-specifications

GENERAL 2G Network GSM 850 / 900 / 1800 / 1900

3G Network HSDPA 850 / 900 / 1900 / 2100

Announced 2011, February

Status Available. Released 2011, April

SIZE Dimensions 125.3 x 66.1 x 8.5 mm

Weight 116 g

DISPLAY Type Super AMOLED Plus capacitive touchscreen, 16M colors

Size 480 x 800 pixels, 4.3 inches (~217 ppi pixel density)

Multitouch Yes

Protection Corning Gorilla Glass

- TouchWiz UI v4.0

- Touch-sensitive controls

SOUND Alert types Vibration; MP3, WAV ringtones

Loudspeaker Yes

3.5mm jack Yes

MEMORY Card slot microSD, up to 32GB, 8 GB included, buy memory

Internal 16GB/32GB storage, 1 GB RAM

DATA GPRS Class 12 (4+1/3+2/2+3/1+4 slots), 32 - 48 kbps

EDGE Class 12

Speed HSDPA, 21 Mbps; HSUPA, 5.76 Mbps

WLAN Wi-Fi 802.11 a/b/g/n, DLNA, Wi-Fi Direct, Wi-Fi hotspot

Bluetooth Yes, v3.0+HS

NFC Optional

USB Yes, v2.0 microUSB (MHL), USB On-the-go

CAMERA Primary 8 MP, 3264x2448 pixels, autofocus, LED flash, check quality

Features Geo-tagging, touch focus, face and smile detection, image stabilization

Video Yes, 1080p@30fps, check quality

Secondary Yes, 2 MP

FEATURES OS Android OS, v2.3 (Gingerbread), planned upgrade to v4.0

Chipset Exynos

CPU Dual-core 1.2 GHz Cortex-A9

GPU Mali-400MP

Sensors Accelerometer, gyro, proximity, compass

Messaging SMS(threaded view), MMS, Email, Push Mail, IM, RSS

Browser HTML, Adobe Flash

Radio Stereo FM radio with RDS

GPS Yes, with A-GPS support

Java Yes, via Java MIDP emulator

Colors Black, White, Pink

- Active noise cancellation with dedicated mic

- TV-out (via MHL A/V link)

- SNS integration

- MP4/DivX/XviD/WMV/H.264/H.263 player

- MP3/WAV/eAAC+/AC3/FLAC player

- Organizer

- Image/video editor

- Document editor (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, PDF)

- Google Search, Maps, Gmail,

YouTube, Calendar, Google Talk, Picasa integration

- Voice memo/dial/commands

- Predictive text input (Swype)

BATTERY Standard battery, Li-Ion 1650 mAh

Stand-by Up to 710 h (2G) / Up to 610 h (3G)

Talk time Up to 18 h 20 min (2G) / Up to 8 h 40 min (3G)

MISC SAR US 0.16 W/kg (head) 0.96 W/kg (body)

SAR EU 0.34 W/kg (head)

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

What is Android?

Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications. The Android SDK provides the tools and APIs necessary to begin developing applications on the Android platform using the Java programming language.

Features

Application framework enabling reuse and replacement of components

Dalvik virtual machine optimized for mobile devices

Integrated browser based on the open source WebKit engine

Optimized graphics powered by a custom 2D graphics library; 3D graphics based on the OpenGL ES 1.0 specification (hardware acceleration optional)

SQLite for structured data storage

Media support for common audio, video, and still image formats (MPEG4, H.264, MP3, AAC, AMR, JPG, PNG, GIF)

GSM Telephony (hardware dependent)

Bluetooth, EDGE, 3G, and WiFi (hardware dependent)

Camera, GPS, compass, and accelerometer (hardware dependent)

Rich development environment including a device emulator, tools for debugging, memory and performance profiling, and a plugin for the Eclipse IDE

Android Architecture

The following diagram shows the major components of the Android operating system. Each section is described in more detail below.

Applications

Android will ship with a set of core applications including an email client, SMS program, calendar, maps, browser, contacts, and others. All applications are written using the Java programming language.

Application Framework

By providing an open development platform, Android offers developers the ability to build extremely rich and innovative applications. Developers are free to take advantage of the device hardware, access location information, run background services, set alarms, add notifications to the status bar, and much, much more.

Developers have full access to the same framework APIs used by the core applications. The application architecture is designed to simplify the reuse of components; any application can publish its capabilities and any other application may then make use of those capabilities (subject to security constraints enforced by the framework). This same mechanism allows components to be replaced by the user.

Underlying all applications is a set of services and systems, including:

A rich and extensible set of Views that can be used to build an application, including lists, grids, text boxes, buttons, and even an embeddable web browser

Content Providers that enable applications to access data from other applications (such as Contacts), or to share their own data

A Resource Manager, providing access to non-code resources such as localized strings, graphics, and layout files

A Notification Manager that enables all applications to display custom alerts in the status bar

An Activity Manager that manages the lifecycle of applications and provides a common navigation backstack

For more details and a walkthrough of an application, see the Notepad Tutorial.

Libraries

Android includes a set of C/C++ libraries used by various components of the Android system. These capabilities are exposed to developers through the Android application framework. Some of the core libraries are listed below:

System C library - a BSD-derived implementation of the standard C system library (libc), tuned for embedded Linux-based devices

Media Libraries - based on PacketVideo's OpenCORE; the libraries support playback and recording of many popular audio and video formats, as well as static image files, including MPEG4, H.264, MP3, AAC, AMR, JPG, and PNG

Surface Manager - manages access to the display subsystem and seamlessly composites 2D and 3D graphic layers from multiple applications

LibWebCore - a modern web browser engine which powers both the Android browser and an embeddable web view

SGL - the underlying 2D graphics engine

3D libraries - an implementation based on OpenGL ES 1.0 APIs; the libraries use either hardware 3D acceleration (where available) or the included, highly optimized 3D software rasterizer

FreeType - bitmap and vector font rendering

SQLite - a powerful and lightweight relational database engine available to all applications

Android Runtime

Android includes a set of core libraries that provides most of the functionality available in the core libraries of the Java programming language.

Every Android application runs in its own process, with its own instance of the Dalvik virtual machine. Dalvik has been written so that a device can run multiple VMs efficiently. The Dalvik VM executes files in the Dalvik Executable (.dex) format which is optimized for minimal memory footprint. The VM is register-based, and runs classes compiled by a Java language compiler that have been transformed into the .dex format by the included "dx" tool.

The Dalvik VM relies on the Linux kernel for underlying functionality such as threading and low-level memory management.

Linux Kernel

Android relies on Linux version 2.6 for core system services such as security, memory management, process management, network stack, and driver model. The kernel also acts as an abstraction layer between the hardware and the rest of the software stack.

Idea NetSetter USB

Idea NetSetter USB

Idea Cellular has launched the new Net Setter EG612 USB Modem (usable with both desktops & Laptops) with data, & SMS facility. It is a conveniently slim & stylish solution for internet access on the move. USB modem is a dedicated data access (GPRS) device to be used with desktops / laptops for wireless internet (GPRS) access.

Idea Net Setter is a terminal available for high-speed wireless network access, with which the users can access the Internet in the wireless way at home, office, outdoor sites and so on.

3G NetSetter is launched at an aggressive price point of Rs.1999/- (MRP)

Please note: Please note: Netsetter Price for Andhra Pradesh & Maharashtra &Goa is at Rs.1600/-(MRP).

Salient Features of 3G NetSetter

Speed - 3G NetSetter support speed of up to 3.6Mbps on HSDPA network and is backward compatible on our current EDGE/GPRS Network. On the current 2G environment subscribers will continue to experience EDGE speeds of up to 236.8 Kbps.

SIM Lock - 3G NetSetter is being launched with a unique SIM Lock functionality wherein the first SIM inserted in the device will be locked with the particular NetSetter device, this will help us address current issues like subscribers not using bundled SIMs and using SIM cards with mobile GPRS plan etc.

USSD Support - 3G NetSetter will enable Pre-paid subscribers to check pre-paid balance though one click USSD option instead of the current SMS mode .

Operating System - 3G NetSetter support all existing and new operating systems like Windows 7, Mac and Linux (limited versions)

Other Features:-

Size: 71.5×26×11mm

HSUPA/HSDPA/UMTS 2100MHz

EDGE/GPRS/GSM 850/900/1800/1900MHz;

HSDPA 3.6M

Data / SMS / USSD support

Invoke browser option

Rx Diversity (Optional)

Improved design

Compatible with Windows 2000/XP/Vista/7, Mac, and Linux OS (limited versions)

Micro SD Card Slot

2 years warranty

The Idea Net Setter supports the following standards:

Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM)

General Packet Radio Service (GPRS)

Enhanced Data Rates for Global Evolution (EDGE)

The Idea Net Setter supports the following services:

Data service

Short message service (SMS)

The EDGE peak rate and effective peak rate are 247kbit/s and 236.8 kbit/s respectively; the GPRS peak rate is 85.6 kbit/s.The IDEA Net Setter is connected to a portable computer or PC by a USB interface. In the service area of the EDGE/GPRS/GSM network, user can wirelessly surf the Internet, send/receive messages and emails. With the high speed, reliable performance, and easy operation of the IDEA Net Setter, the users can enjoy much more in experiencing the wireless network.

The product is priced at Rs. 2490/- MRP (incl of taxes)

Features

GSM/GPRS/EDGE 850 MHz/900 MHz/1800 MHz/1900 MHz

Global roaming

GRPS/EDGE Class1~Class12

Data and SMS capabilities.

SMS services (group sending and editing the extra-long messages)

Plug & Play function, Zero CD installation

SIM-lock function

Value Proposition

Service Tax will be charged as applicable

SMS Local / National / International will be charged as Rs. 1/- /Rs. 1.50/- / Rs. 5/-respectively.

Home tariff will be applicable while roaming on Idea network, on non-idea networks charge of 10 paise / 10 kB is applicable towards GPRS usage.

Postpaid: International Roaming Tariff - Rs 5 /10 kb

Prepaid : International Roaming Tariff -Upload + Download charged at Rs.10 / 10 Kb for all zones

Kerala Plus One Improvement Results 2011

Kerala Higher Secondary Board is expected to announce plus one improvement test results 2011 in the month of November.

Plus One Improvement Results 2011

Kerala Plus One Improvement Test Results will be made available on the official website of Kerala Higher Secondary Board

Kerala Higher Secondary Board

Consistent with the National Education Policy of 1986, Government decided to delink Pre-degree Courses from colleges in a phased manner and to introduce 10+2 system in the High Schools of Kerala. Accordingly, Kerala Higher Secondary Department was formed in 1990 and the course was introduced in 31 selected Government high schools in the State to reorganize secondary and collegiate education. The two-year course was named as Higher Secondary (Plus Two) Course.

The main objective of the department is to impart best quality higher education to the eligible students of the State who complete their SSLC/equivalent level education. In order to achieve this objective, the department conducts courses in Science, Humanities and Commerce streams in the Higher Secondary Schools and imparts timely training to teachers. The process of de-linking Pre-degree courses from colleges was completed by the academic year 2000-2001. A total of 1907 Higher Secondary Schools are functioning in the State; 760 in government sector, 686 in aided sector and 461 in unaided sector. The system is offering Science, Humanities and Commerce stream courses to 6.5 lakh students. There are more than 20,000 teachers in government and aided sectors.

How To Become A Hacker???

Why This Document?

As editor of the Jargon File and author of a few other well-known documents of similar nature, I often get email requests from enthusiastic network newbies asking (in effect) "how can I learn to be a wizardly hacker?". Back in 1996 I noticed that there didn't seem to be any other FAQs or web documents that addressed this vital question, so I started this one. A lot of hackers now consider it definitive, and I suppose that means it is. Still, I don't claim to be the exclusive authority on this topic; if you don't like what you read here, write your own.

If you are reading a snapshot of this document offline, the current version lives at http://catb.org/~esr/faqs/hacker-howto.html.

Note: there is a list of Frequently Asked Questions at the end of this document. Please read these—twice—before mailing me any questions about this document.

Numerous translations of this document are available: Arabic Belorussian Chinese (Simplified), Danish, Dutch, Estonian, German, Greek Italian Hebrew, Norwegian, Portuguese (Brazilian), Romanian Spanish, Turkish, and Swedish. Note that since this document changes occasionally, they may be out of date to varying degrees.

The five-dots-in-nine-squares diagram that decorates this document is called a glider. It is a simple pattern with some surprising properties in a mathematical simulation called Life that has fascinated hackers for many years. I think it makes a good visual emblem for what hackers are like — abstract, at first a bit mysterious-seeming, but a gateway to a whole world with an intricate logic of its own. Read more about the glider emblem here.

What Is a Hacker?

The Jargon File contains a bunch of definitions of the term ‘hacker’, most having to do with technical adeptness and a delight in solving problems and overcoming limits. If you want to know how to become a hacker, though, only two are really relevant.

There is a community, a shared culture, of expert programmers and networking wizards that traces its history back through decades to the first time-sharing minicomputers and the earliest ARPAnet experiments. The members of this culture originated the term ‘hacker’. Hackers built the Internet. Hackers made the Unix operating system what it is today. Hackers run Usenet. Hackers make the World Wide Web work. If you are part of this culture, if you have contributed to it and other people in it know who you are and call you a hacker, you're a hacker.

The hacker mind-set is not confined to this software-hacker culture. There are people who apply the hacker attitude to other things, like electronics or music — actually, you can find it at the highest levels of any science or art. Software hackers recognize these kindred spirits elsewhere and may call them ‘hackers’ too — and some claim that the hacker nature is really independent of the particular medium the hacker works in. But in the rest of this document we will focus on the skills and attitudes of software hackers, and the traditions of the shared culture that originated the term ‘hacker’.

There is another group of people who loudly call themselves hackers, but aren't. These are people (mainly adolescent males) who get a kick out of breaking into computers and phreaking the phone system. Real hackers call these people ‘crackers’ and want nothing to do with them. Real hackers mostly think crackers are lazy, irresponsible, and not very bright, and object that being able to break security doesn't make you a hacker any more than being able to hotwire cars makes you an automotive engineer. Unfortunately, many journalists and writers have been fooled into using the word ‘hacker’ to describe crackers; this irritates real hackers no end.

The basic difference is this: hackers build things, crackers break them.

If you want to be a hacker, keep reading. If you want to be a cracker, go read the alt.2600 newsgroup and get ready to do five to ten in the slammer after finding out you aren't as smart as you think you are. And that's all I'm going to say about crackers.

The Hacker Attitude

1. The world is full of fascinating problems waiting to be solved.

2. No problem should ever have to be solved twice.

3. Boredom and drudgery are evil.

4. Freedom is good.

5. Attitude is no substitute for competence.

Hackers solve problems and build things, and they believe in freedom and voluntary mutual help. To be accepted as a hacker, you have to behave as though you have this kind of attitude yourself. And to behave as though you have the attitude, you have to really believe the attitude.

But if you think of cultivating hacker attitudes as just a way to gain acceptance in the culture, you'll miss the point. Becoming the kind of person who believes these things is important for you — for helping you learn and keeping you motivated. As with all creative arts, the most effective way to become a master is to imitate the mind-set of masters — not just intellectually but emotionally as well.

Or, as the following modern Zen poem has it:

To follow the path:

look to the master,

follow the master,

walk with the master,

see through the master,

become the master.

So, if you want to be a hacker, repeat the following things until you believe them:

1. The world is full of fascinating problems waiting to be solved.

Being a hacker is lots of fun, but it's a kind of fun that takes lots of effort. The effort takes motivation. Successful athletes get their motivation from a kind of physical delight in making their bodies perform, in pushing themselves past their own physical limits. Similarly, to be a hacker you have to get a basic thrill from solving problems, sharpening your skills, and exercising your intelligence.

If you aren't the kind of person that feels this way naturally, you'll need to become one in order to make it as a hacker. Otherwise you'll find your hacking energy is sapped by distractions like sex, money, and social approval.

(You also have to develop a kind of faith in your own learning capacity — a belief that even though you may not know all of what you need to solve a problem, if you tackle just a piece of it and learn from that, you'll learn enough to solve the next piece — and so on, until you're done.)

2. No problem should ever have to be solved twice.

Creative brains are a valuable, limited resource. They shouldn't be wasted on re-inventing the wheel when there are so many fascinating new problems waiting out there.

To behave like a hacker, you have to believe that the thinking time of other hackers is precious — so much so that it's almost a moral duty for you to share information, solve problems and then give the solutions away just so other hackers can solve new problems instead of having to perpetually re-address old ones.

Note, however, that "No problem should ever have to be solved twice." does not imply that you have to consider all existing solutions sacred, or that there is only one right solution to any given problem. Often, we learn a lot about the problem that we didn't know before by studying the first cut at a solution. It's OK, and often necessary, to decide that we can do better. What's not OK is artificial technical, legal, or institutional barriers (like closed-source code) that prevent a good solution from being re-used and force people to re-invent wheels.

(You don't have to believe that you're obligated to give all your creative product away, though the hackers that do are the ones that get most respect from other hackers. It's consistent with hacker values to sell enough of it to keep you in food and rent and computers. It's fine to use your hacking skills to support a family or even get rich, as long as you don't forget your loyalty to your art and your fellow hackers while doing it.)

3. Boredom and drudgery are evil.

Hackers (and creative people in general) should never be bored or have to drudge at stupid repetitive work, because when this happens it means they aren't doing what only they can do — solve new problems. This wastefulness hurts everybody. Therefore boredom and drudgery are not just unpleasant but actually evil.

To behave like a hacker, you have to believe this enough to want to automate away the boring bits as much as possible, not just for yourself but for everybody else (especially other hackers).

(There is one apparent exception to this. Hackers will sometimes do things that may seem repetitive or boring to an observer as a mind-clearing exercise, or in order to acquire a skill or have some particular kind of experience you can't have otherwise. But this is by choice — nobody who can think should ever be forced into a situation that bores them.)

4. Freedom is good.

Hackers are naturally anti-authoritarian. Anyone who can give you orders can stop you from solving whatever problem you're being fascinated by — and, given the way authoritarian minds work, will generally find some appallingly stupid reason to do so. So the authoritarian attitude has to be fought wherever you find it, lest it smother you and other hackers.

(This isn't the same as fighting all authority. Children need to be guided and criminals restrained. A hacker may agree to accept some kinds of authority in order to get something he wants more than the time he spends following orders. But that's a limited, conscious bargain; the kind of personal surrender authoritarians want is not on offer.)

Authoritarians thrive on censorship and secrecy. And they distrust voluntary cooperation and information-sharing — they only like ‘cooperation’ that they control. So to behave like a hacker, you have to develop an instinctive hostility to censorship, secrecy, and the use of force or deception to compel responsible adults. And you have to be willing to act on that belief.

5. Attitude is no substitute for competence.

To be a hacker, you have to develop some of these attitudes. But copping an attitude alone won't make you a hacker, any more than it will make you a champion athlete or a rock star. Becoming a hacker will take intelligence, practice, dedication, and hard work.

Therefore, you have to learn to distrust attitude and respect competence of every kind. Hackers won't let posers waste their time, but they worship competence — especially competence at hacking, but competence at anything is valued. Competence at demanding skills that few can master is especially good, and competence at demanding skills that involve mental acuteness, craft, and concentration is best.

If you revere competence, you'll enjoy developing it in yourself — the hard work and dedication will become a kind of intense play rather than drudgery. That attitude is vital to becoming a hacker.

Basic Hacking Skills

1. Learn how to program.

2. Get one of the open-source Unixes and learn to use and run it.

3. Learn how to use the World Wide Web and write HTML.

4. If you don't have functional English, learn it.

The hacker attitude is vital, but skills are even more vital. Attitude is no substitute for competence, and there's a certain basic toolkit of skills which you have to have before any hacker will dream of calling you one.

This toolkit changes slowly over time as technology creates new skills and makes old ones obsolete. For example, it used to include programming in machine language, and didn't until recently involve HTML. But right now it pretty clearly includes the following:

1. Learn how to program.

This, of course, is the fundamental hacking skill. If you don't know any computer languages, I recommend starting with Python. It is cleanly designed, well documented, and relatively kind to beginners. Despite being a good first language, it is not just a toy; it is very powerful and flexible and well suited for large projects. I have written a more detailed evaluation of Python. Good tutorials are available at the Python web site.

I used to recommend Java as a good language to learn early, but this critique has changed my mind (search for “The Pitfalls of Java as a First Programming Language†within it). A hacker cannot, as they devastatingly put it “approach problem-solving like a plumber in a hardware storeâ€; you have to know what the components actually do. Now I think it is probably best to learn C and Lisp first, then Java.

There is perhaps a more general point here. If a language does too much for you, it may be simultaneously a good tool for production and a bad one for learning. It's not only languages that have this problem; web application frameworks like RubyOnRails, CakePHP, Django may make it too easy to reach a superficial sort of understanding that will leave you without resources when you have to tackle a hard problem, or even just debug the solution to an easy one.

If you get into serious programming, you will have to learn C, the core language of Unix. C++ is very closely related to C; if you know one, learning the other will not be difficult. Neither language is a good one to try learning as your first, however. And, actually, the more you can avoid programming in C the more productive you will be.

C is very efficient, and very sparing of your machine's resources. Unfortunately, C gets that efficiency by requiring you to do a lot of low-level management of resources (like memory) by hand. All that low-level code is complex and bug-prone, and will soak up huge amounts of your time on debugging. With today's machines as powerful as they are, this is usually a bad tradeoff — it's smarter to use a language that uses the machine's time less efficiently, but your time much more efficiently. Thus, Python.

Other languages of particular importance to hackers include Perl and LISP. Perl is worth learning for practical reasons; it's very widely used for active web pages and system administration, so that even if you never write Perl you should learn to read it. Many people use Perl in the way I suggest you should use Python, to avoid C programming on jobs that don't require C's machine efficiency. You will need to be able to understand their code.

LISP is worth learning for a different reason — the profound enlightenment experience you will have when you finally get it. That experience will make you a better programmer for the rest of your days, even if you never actually use LISP itself a lot. (You can get some beginning experience with LISP fairly easily by writing and modifying editing modes for the Emacs text editor, or Script-Fu plugins for the GIMP.)

It's best, actually, to learn all five of Python, C/C++, Java, Perl, and LISP. Besides being the most important hacking languages, they represent very different approaches to programming, and each will educate you in valuable ways.

But be aware that you won't reach the skill level of a hacker or even merely a programmer simply by accumulating languages — you need to learn how to think about programming problems in a general way, independent of any one language. To be a real hacker, you need to get to the point where you can learn a new language in days by relating what's in the manual to what you already know. This means you should learn several very different languages.

I can't give complete instructions on how to learn to program here — it's a complex skill. But I can tell you that books and courses won't do it — many, maybe most of the best hackers are self-taught. You can learn language features — bits of knowledge — from books, but the mind-set that makes that knowledge into living skill can be learned only by practice and apprenticeship. What will do it is (a) reading code and (b) writing code.

Peter Norvig, who is one of Google's top hackers and the co-author of the most widely used textbook on AI, has written an excellent essay called Teach Yourself Programming in Ten Years. His "recipe for programming success" is worth careful attention.

Learning to program is like learning to write good natural language. The best way to do it is to read some stuff written by masters of the form, write some things yourself, read a lot more, write a little more, read a lot more, write some more ... and repeat until your writing begins to develop the kind of strength and economy you see in your models.

Finding good code to read used to be hard, because there were few large programs available in source for fledgeling hackers to read and tinker with. This has changed dramatically; open-source software, programming tools, and operating systems (all built by hackers) are now widely available. Which brings me neatly to our next topic...

2. Get one of the open-source Unixes and learn to use and run it.

I'll assume you have a personal computer or can get access to one. (Take a moment to appreciate how much that means. The hacker culture originally evolved back when computers were so expensive that individuals could not own them.) The single most important step any newbie can take toward acquiring hacker skills is to get a copy of Linux or one of the BSD-Unixes or OpenSolaris, install it on a personal machine, and run it.

Yes, there are other operating systems in the world besides Unix. But they're distributed in binary — you can't read the code, and you can't modify it. Trying to learn to hack on a Microsoft Windows machine or under any other closed-source system is like trying to learn to dance while wearing a body cast.

Under Mac OS X it's possible, but only part of the system is open source — you're likely to hit a lot of walls, and you have to be careful not to develop the bad habit of depending on Apple's proprietary code. If you concentrate on the Unix under the hood you can learn some useful things.

Unix is the operating system of the Internet. While you can learn to use the Internet without knowing Unix, you can't be an Internet hacker without understanding Unix. For this reason, the hacker culture today is pretty strongly Unix-centered. (This wasn't always true, and some old-time hackers still aren't happy about it, but the symbiosis between Unix and the Internet has become strong enough that even Microsoft's muscle doesn't seem able to seriously dent it.)

So, bring up a Unix — I like Linux myself but there are other ways (and yes, you can run both Linux and Microsoft Windows on the same machine). Learn it. Run it. Tinker with it. Talk to the Internet with it. Read the code. Modify the code. You'll get better programming tools (including C, LISP, Python, and Perl) than any Microsoft operating system can dream of hosting, you'll have fun, and you'll soak up more knowledge than you realize you're learning until you look back on it as a master hacker.

For more about learning Unix, see The Loginataka. You might also want to have a look at The Art Of Unix Programming.

To get your hands on a Linux, see the Linux Online! site; you can download from there or (better idea) find a local Linux user group to help you with installation.

During the first ten years of this HOWTO's life, I reported that from a new user's point of view, all Linux distributions are almost equivalent. But in 2006-2007, an actual best choice emerged: Ubuntu. While other distros have their own areas of strength, Ubuntu is far and away the most accessible to Linux newbies.

You can find BSD Unix help and resources at www.bsd.org.

A good way to dip your toes in the water is to boot up what Linux fans call a live CD, a distribution that runs entirely off a CD without having to modify your hard disk. This will be slow, because CDs are slow, but it's a way to get a look at the possibilities without having to do anything drastic.

I have written a primer on the basics of Unix and the Internet.

I used to recommend against installing either Linux or BSD as a solo project if you're a newbie. Nowadays the installers have gotten good enough that doing it entirely on your own is possible, even for a newbie. Nevertheless, I still recommend making contact with your local Linux user's group and asking for help. It can't hurt, and may smooth the process.

3. Learn how to use the World Wide Web and write HTML.

Most of the things the hacker culture has built do their work out of sight, helping run factories and offices and universities without any obvious impact on how non-hackers live. The Web is the one big exception, the huge shiny hacker toy that even politicians admit has changed the world. For this reason alone (and a lot of other good ones as well) you need to learn how to work the Web.

This doesn't just mean learning how to drive a browser (anyone can do that), but learning how to write HTML, the Web's markup language. If you don't know how to program, writing HTML will teach you some mental habits that will help you learn. So build a home page. Try to stick to XHTML, which is a cleaner language than classic HTML. (There are good beginner tutorials on the Web; here's one.)

But just having a home page isn't anywhere near good enough to make you a hacker. The Web is full of home pages. Most of them are pointless, zero-content sludge — very snazzy-looking sludge, mind you, but sludge all the same (for more on this see The HTML Hell Page).

To be worthwhile, your page must have content — it must be interesting and/or useful to other hackers. And that brings us to the next topic...

4. If you don't have functional English, learn it.

As an American and native English-speaker myself, I have previously been reluctant to suggest this, lest it be taken as a sort of cultural imperialism. But several native speakers of other languages have urged me to point out that English is the working language of the hacker culture and the Internet, and that you will need to know it to function in the hacker community.

Back around 1991 I learned that many hackers who have English as a second language use it in technical discussions even when they share a birth tongue; it was reported to me at the time that English has a richer technical vocabulary than any other language and is therefore simply a better tool for the job. For similar reasons, translations of technical books written in English are often unsatisfactory (when they get done at all).

Linus Torvalds, a Finn, comments his code in English (it apparently never occurred to him to do otherwise). His fluency in English has been an important factor in his ability to recruit a worldwide community of developers for Linux. It's an example worth following.

Being a native English-speaker does not guarantee that you have language skills good enough to function as a hacker. If your writing is semi-literate, ungrammatical, and riddled with misspellings, many hackers (including myself) will tend to ignore you. While sloppy writing does not invariably mean sloppy thinking, we've generally found the correlation to be strong — and we have no use for sloppy thinkers. If you can't yet write competently, learn to.

Status in the Hacker Culture

1. Write open-source software

2. Help test and debug open-source software

3. Publish useful information

4. Help keep the infrastructure working

5. Serve the hacker culture itself

Like most cultures without a money economy, hackerdom runs on reputation. You're trying to solve interesting problems, but how interesting they are, and whether your solutions are really good, is something that only your technical peers or superiors are normally equipped to judge.

Accordingly, when you play the hacker game, you learn to keep score primarily by what other hackers think of your skill (this is why you aren't really a hacker until other hackers consistently call you one). This fact is obscured by the image of hacking as solitary work; also by a hacker-cultural taboo (gradually decaying since the late 1990s but still potent) against admitting that ego or external validation are involved in one's motivation at all.

Specifically, hackerdom is what anthropologists call a gift culture. You gain status and reputation in it not by dominating other people, nor by being beautiful, nor by having things other people want, but rather by giving things away. Specifically, by giving away your time, your creativity, and the results of your skill.

There are basically five kinds of things you can do to be respected by hackers:

1. Write open-source software

The first (the most central and most traditional) is to write programs that other hackers think are fun or useful, and give the program sources away to the whole hacker culture to use.

(We used to call these works “free softwareâ€, but this confused too many people who weren't sure exactly what “free†was supposed to mean. Most of us now prefer the term “open-source†software).

Hackerdom's most revered demigods are people who have written large, capable programs that met a widespread need and given them away, so that now everyone uses them.

But there's a bit of a fine historical point here. While hackers have always looked up to the open-source developers among them as our community's hardest core, before the mid-1990s most hackers most of the time worked on closed source. This was still true when I wrote the first version of this HOWTO in 1996; it took the mainstreaming of open-source software after 1997 to change things. Today, "the hacker community" and "open-source developers" are two descriptions for what is essentially the same culture and population — but it is worth remembering that this was not always so. (For more on this, see the section called “Historical Note: Hacking, Open Source, and Free Softwareâ€.)

2. Help test and debug open-source software

They also serve who stand and debug open-source software. In this imperfect world, we will inevitably spend most of our software development time in the debugging phase. That's why any open-source author who's thinking will tell you that good beta-testers (who know how to describe symptoms clearly, localize problems well, can tolerate bugs in a quickie release, and are willing to apply a few simple diagnostic routines) are worth their weight in rubies. Even one of these can make the difference between a debugging phase that's a protracted, exhausting nightmare and one that's merely a salutary nuisance.

If you're a newbie, try to find a program under development that you're interested in and be a good beta-tester. There's a natural progression from helping test programs to helping debug them to helping modify them. You'll learn a lot this way, and generate good karma with people who will help you later on.

3. Publish useful information

Another good thing is to collect and filter useful and interesting information into web pages or documents like Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) lists, and make those generally available.

Maintainers of major technical FAQs get almost as much respect as open-source authors.

4. Help keep the infrastructure working

The hacker culture (and the engineering development of the Internet, for that matter) is run by volunteers. There's a lot of necessary but unglamorous work that needs done to keep it going — administering mailing lists, moderating newsgroups, maintaining large software archive sites, developing RFCs and other technical standards.

People who do this sort of thing well get a lot of respect, because everybody knows these jobs are huge time sinks and not as much fun as playing with code. Doing them shows dedication.

5. Serve the hacker culture itself

Finally, you can serve and propagate the culture itself (by, for example, writing an accurate primer on how to become a hacker :-)). This is not something you'll be positioned to do until you've been around for while and become well-known for one of the first four things.

The hacker culture doesn't have leaders, exactly, but it does have culture heroes and tribal elders and historians and spokespeople. When you've been in the trenches long enough, you may grow into one of these. Beware: hackers distrust blatant ego in their tribal elders, so visibly reaching for this kind of fame is dangerous. Rather than striving for it, you have to sort of position yourself so it drops in your lap, and then be modest and gracious about your status.

The Hacker/Nerd Connection

Contrary to popular myth, you don't have to be a nerd to be a hacker. It does help, however, and many hackers are in fact nerds. Being something of a social outcast helps you stay concentrated on the really important things, like thinking and hacking.

For this reason, many hackers have adopted the label ‘geek’ as a badge of pride — it's a way of declaring their independence from normal social expectations (as well as a fondness for other things like science fiction and strategy games that often go with being a hacker). The term 'nerd' used to be used this way back in the 1990s, back when 'nerd' was a mild pejorative and 'geek' a rather harsher one; sometime after 2000 they switched places, at least in U.S. popular culture, and there is now even a significant geek-pride culture among people who aren't techies.

If you can manage to concentrate enough on hacking to be good at it and still have a life, that's fine. This is a lot easier today than it was when I was a newbie in the 1970s; mainstream culture is much friendlier to techno-nerds now. There are even growing numbers of people who realize that hackers are often high-quality lover and spouse material.

If you're attracted to hacking because you don't have a life, that's OK too — at least you won't have trouble concentrating. Maybe you'll get a life later on.

Points For Style

Again, to be a hacker, you have to enter the hacker mindset. There are some things you can do when you're not at a computer that seem to help. They're not substitutes for hacking (nothing is) but many hackers do them, and feel that they connect in some basic way with the essence of hacking.

Learn to write your native language well. Though it's a common stereotype that programmers can't write, a surprising number of hackers (including all the most accomplished ones I know of) are very able writers.

Read science fiction. Go to science fiction conventions (a good way to meet hackers and proto-hackers).

Train in a martial-arts form. The kind of mental discipline required for martial arts seems to be similar in important ways to what hackers do. The most popular forms among hackers are definitely Asian empty-hand arts such as Tae Kwon Do, various forms of Karate, Kung Fu, Aikido, or Ju Jitsu. Western fencing and Asian sword arts also have visible followings. In places where it's legal, pistol shooting has been rising in popularity since the late 1990s. The most hackerly martial arts are those which emphasize mental discipline, relaxed awareness, and control, rather than raw strength, athleticism, or physical toughness.

Study an actual meditation discipline. The perennial favorite among hackers is Zen (importantly, it is possible to benefit from Zen without acquiring a religion or discarding one you already have). Other styles may work as well, but be careful to choose one that doesn't require you to believe crazy things.

Develop an analytical ear for music. Learn to appreciate peculiar kinds of music. Learn to play some musical instrument well, or how to sing.

Develop your appreciation of puns and wordplay.

The more of these things you already do, the more likely it is that you are natural hacker material. Why these things in particular is not completely clear, but they're connected with a mix of left- and right-brain skills that seems to be important; hackers need to be able to both reason logically and step outside the apparent logic of a problem at a moment's notice.

Work as intensely as you play and play as intensely as you work. For true hackers, the boundaries between "play", "work", "science" and "art" all tend to disappear, or to merge into a high-level creative playfulness. Also, don't be content with a narrow range of skills. Though most hackers self-describe as programmers, they are very likely to be more than competent in several related skills — system administration, web design, and PC hardware troubleshooting are common ones. A hacker who's a system administrator, on the other hand, is likely to be quite skilled at script programming and web design. Hackers don't do things by halves; if they invest in a skill at all, they tend to get very good at it.

Finally, a few things not to do.

Don't use a silly, grandiose user ID or screen name.

Don't get in flame wars on Usenet (or anywhere else).

Don't call yourself a ‘cyberpunk’, and don't waste your time on anybody who does.

Don't post or email writing that's full of spelling errors and bad grammar.

The only reputation you'll make doing any of these things is as a twit. Hackers have long memories — it could take you years to live your early blunders down enough to be accepted.

The problem with screen names or handles deserves some amplification. Concealing your identity behind a handle is a juvenile and silly behavior characteristic of crackers, warez d00dz, and other lower life forms. Hackers don't do this; they're proud of what they do and want it associated with their real names. So if you have a handle, drop it. In the hacker culture it will only mark you as a loser.

Historical Note: Hacking, Open Source, and Free Software

When I originally wrote this how-to in late 1996, some of the conditions around it were very different from the way they look today. A few words about these changes may help clarify matters for people who are confused about the relationship of open source, free software, and Linux to the hacker community. If you are not curious about this, you can skip straight to the FAQ and bibliography from here.

The hacker ethos and community as I have described it here long predates the emergence of Linux after 1990; I first became involved with it around 1976, and, its roots are readily traceable back to the early 1960s. But before Linux, most hacking was done on either proprietary operating systems or a handful of quasi-experimental homegrown systems like MIT's ITS that were never deployed outside of their original academic niches. While there had been some earlier (pre-Linux) attempts to change this situation, their impact was at best very marginal and confined to communities of dedicated true believers which were tiny minorities even within the hacker community, let alone with respect to the larger world of software in general.

What is now called "open source" goes back as far as the hacker community does, but until 1985 it was an unnamed folk practice rather than a conscious movement with theories and manifestos attached to it. This prehistory ended when, in 1985, arch-hacker Richard Stallman ("RMS") tried to give it a name — "free software". But his act of naming was also an act of claiming; he attached ideological baggage to the "free software" label which much of the existing hacker community never accepted. As a result, the "free software" label was loudly rejected by a substantial minority of the hacker community (especially among those associated with BSD Unix), and used with serious but silent reservations by a majority of the remainder (including myself).

Despite these reservations, RMS's claim to define and lead the hacker community under the "free software" banner broadly held until the mid-1990s. It was seriously challenged only by the rise of Linux. Linux gave open-source development a natural home. Many projects issued under terms we would now call open-source migrated from proprietary Unixes to Linux. The community around Linux grew explosively, becoming far larger and more heterogenous than the pre-Linux hacker culture. RMS determinedly attempted to co-opt all this activity into his "free software" movement, but was thwarted by both the exploding diversity of the Linux community and the public skepticism of its founder, Linus Torvalds. Torvalds continued to use the term "free software" for lack of any alternative, but publicly rejected RMS's ideological baggage. Many younger hackers followed suit.

In 1996, when I first published this Hacker HOWTO, the hacker community was rapidly reorganizing around Linux and a handful of other open-source operating systems (notably those descended from BSD Unix). Community memory of the fact that most of us had spent decades developing closed-source software on closed-source operating systems had not yet begun to fade, but that fact was already beginning to seem like part of a dead past; hackers were, increasingly, defining themselves as hackers by their attachments to open-source projects such as Linux or Apache.

The term "open source", however, had not yet emerged; it would not do so until early 1998. When it did, most of hacker community adopted it within the following six months; the exceptions were a minority ideologically attached to the term "free software". Since 1998, and especially after about 2003, the identification of 'hacking' with 'open-source (and free software) development' has become extremely close. Today there is little point in attempting to distinguish between these categories, and it seems unlikely that will change in the future.

It is worth remembering, however, that this was not always so.

Other Resources

Paul Graham has written an essay called Great Hackers, and another on Undergraduation, in which he speaks much wisdom.

There is a document called How To Be A Programmer that is an excellent complement to this one. It has valuable advice not just about coding and skillsets, but about how to function on a programming team.

I have also written A Brief History Of Hackerdom.

I have written a paper, The Cathedral and the Bazaar, which explains a lot about how the Linux and open-source cultures work. I have addressed this topic even more directly in its sequel Homesteading the Noosphere.

Rick Moen has written an excellent document on how to run a Linux user group.

Rick Moen and I have collaborated on another document on How To Ask Smart Questions. This will help you seek assistance in a way that makes it more likely that you will actually get it.

If you need instruction in the basics of how personal computers, Unix, and the Internet work, see The Unix and Internet Fundamentals HOWTO.

When you release software or write patches for software, try to follow the guidelines in the Software Release Practice HOWTO.

If you enjoyed the Zen poem, you might also like Rootless Root: The Unix Koans of Master Foo.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How do I tell if I am already a hacker?

Q: Will you teach me how to hack?

Q: How can I get started, then?

Q: When do you have to start? Is it too late for me to learn?

Q: How long will it take me to learn to hack?

Q: Is Visual Basic a good language to start with?

Q: Would you help me to crack a system, or teach me how to crack?

Q: How can I get the password for someone else's account?

Q: How can I break into/read/monitor someone else's email?

Q: How can I steal channel op privileges on IRC?

Q: I've been cracked. Will you help me fend off further attacks?

Q: I'm having problems with my Windows software. Will you help me?

Q: Where can I find some real hackers to talk with?

Q: Can you recommend useful books about hacking-related subjects?

Q: Do I need to be good at math to become a hacker?

Q: What language should I learn first?

Q: What kind of hardware do I need?

Q: I want to contribute. Can you help me pick a problem to work on?

Q: Do I need to hate and bash Microsoft?

Q: But won't open-source software leave programmers unable to make a living?

Q: Where can I get a free Unix?

Q:

How do I tell if I am already a hacker?

A:

Ask yourself the following three questions:

Do you speak code, fluently?

Do you identify with the goals and values of the hacker community?

Has a well-established member of the hacker community ever called you a hacker?

If you can answer yes to all three of these questions, you are already a hacker. No two alone are sufficient.

The first test is about skills. You probably pass it if you have the minimum technical skills described earlier in this document. You blow right through it if you have had a substantial amount of code accepted by an open-source development project.

The second test is about attitude. If the five principles of the hacker mindset seemed obvious to you, more like a description of the way you already live than anything novel, you are already halfway to passing it. That's the inward half; the other, outward half is the degree to which you identify with the hacker community's long-term projects.

Here is an incomplete but indicative list of some of those projects: Does it matter to you that Linux improve and spread? Are you passionate about software freedom? Hostile to monopolies? Do you act on the belief that computers can be instruments of empowerment that make the world a richer and more humane place?

But a note of caution is in order here. The hacker community has some specific, primarily defensive political interests — two of them are defending free-speech rights and fending off "intellectual-property" power grabs that would make open source illegal. Some of those long-term projects are civil-liberties organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the outward attitude properly includes support of them. But beyond that, most hackers view attempts to systematize the hacker attitude into an explicit political program with suspicion; we've learned, the hard way, that these attempts are divisive and distracting. If someone tries to recruit you to march on your capitol in the name of the hacker attitude, they've missed the point. The right response is probably “Shut up and show them the code.â€

The third test has a tricky element of recursiveness about it. I observed in the section called “What Is a Hacker?†that being a hacker is partly a matter of belonging to a particular subculture or social network with a shared history, an inside and an outside. In the far past, hackers were a much less cohesive and self-aware group than they are today. But the importance of the social-network aspect has increased over the last thirty years as the Internet has made connections with the core of the hacker subculture easier to develop and maintain. One easy behavioral index of the change is that, in this century, we have our own T-shirts.

Sociologists, who study networks like those of the hacker culture under the general rubric of "invisible colleges", have noted that one characteristic of such networks is that they have gatekeepers — core members with the social authority to endorse new members into the network. Because the "invisible college" that is hacker culture is a loose and informal one, the role of gatekeeper is informal too. But one thing that all hackers understand in their bones is that not every hacker is a gatekeeper. Gatekeepers have to have a certain degree of seniority and accomplishment before they can bestow the title. How much is hard to quantify, but every hacker knows it when they see it.

Q:

Will you teach me how to hack?

A:

Since first publishing this page, I've gotten several requests a week (often several a day) from people to "teach me all about hacking". Unfortunately, I don't have the time or energy to do this; my own hacking projects, and working as an open-source advocate, take up 110% of my time.

Even if I did, hacking is an attitude and skill you basically have to teach yourself. You'll find that while real hackers want to help you, they won't respect you if you beg to be spoon-fed everything they know.

Learn a few things first. Show that you're trying, that you're capable of learning on your own. Then go to the hackers you meet with specific questions.

If you do email a hacker asking for advice, here are two things to know up front. First, we've found that people who are lazy or careless in their writing are usually too lazy and careless in their thinking to make good hackers — so take care to spell correctly, and use good grammar and punctuation, otherwise you'll probably be ignored. Secondly, don't dare ask for a reply to an ISP account that's different from the account you're sending from; we find people who do that are usually thieves using stolen accounts, and we have no interest in rewarding or assisting thievery.

Q:

How can I get started, then?

A:

The best way for you to get started would probably be to go to a LUG (Linux user group) meeting. You can find such groups on the LDP General Linux Information Page; there is probably one near you, possibly associated with a college or university. LUG members will probably give you a Linux if you ask, and will certainly help you install one and get started.

Q:

When do you have to start? Is it too late for me to learn?

A:

Any age at which you are motivated to start is a good age. Most people seem to get interested between ages 15 and 20, but I know of exceptions in both directions.

Q:

How long will it take me to learn to hack?

A:

That depends on how talented you are and how hard you work at it. Most people who try can acquire a respectable skill set in eighteen months to two years, if they concentrate. Don't think it ends there, though; in hacking (as in many other fields) it takes about ten years to achieve mastery. And if you are a real hacker, you will spend the rest of your life learning and perfecting your craft.

Q:

Is Visual Basic a good language to start with?

A:

If you're asking this question, it almost certainly means you're thinking about trying to hack under Microsoft Windows. This is a bad idea in itself. When I compared trying to learn to hack under Windows to trying to learn to dance while wearing a body cast, I wasn't kidding. Don't go there. It's ugly, and it never stops being ugly.

There is a specific problem with Visual Basic; mainly that it's not portable. Though there is a prototype open-source implementations of Visual Basic, the applicable ECMA standards don't cover more than a small set of its programming interfaces. On Windows most of its library support is proprietary to a single vendor (Microsoft); if you aren't extremely careful about which features you use — more careful than any newbie is really capable of being — you'll end up locked into only those platforms Microsoft chooses to support. If you're starting on a Unix, much better languages with better libraries are available. Python, for example.

Also, like other Basics, Visual Basic is a poorly-designed language that will teach you bad programming habits. No, don't ask me to describe them in detail; that explanation would fill a book. Learn a well-designed language instead.

One of those bad habits is becoming dependent on a single vendor's libraries, widgets, and development tools. In general, any language that isn't fully supported under at least Linux or one of the BSDs, and/or at least three different vendors' operating systems, is a poor one to learn to hack in.

Q:

Would you help me to crack a system, or teach me how to crack?

A:

No. Anyone who can still ask such a question after reading this FAQ is too stupid to be educable even if I had the time for tutoring. Any emailed requests of this kind that I get will be ignored or answered with extreme rudeness.

Q:

How can I get the password for someone else's account?

A:

This is cracking. Go away, idiot.

Q:

How can I break into/read/monitor someone else's email?

A:

This is cracking. Get lost, moron.

Q:

How can I steal channel op privileges on IRC?

A:

This is cracking. Begone, cretin.

Q:

I've been cracked. Will you help me fend off further attacks?

A:

No. Every time I've been asked this question so far, it's been from some poor sap running Microsoft Windows. It is not possible to effectively secure Windows systems against crack attacks; the code and architecture simply have too many flaws, which makes securing Windows like trying to bail out a boat with a sieve. The only reliable prevention starts with switching to Linux or some other operating system that is designed to at least be capable of security.

Q:

I'm having problems with my Windows software. Will you help me?

A:

Yes. Go to a DOS prompt and type "format c:". Any problems you are experiencing will cease within a few minutes.

Q:

Where can I find some real hackers to talk with?

A:

The best way is to find a Unix or Linux user's group local to you and go to their meetings (you can find links to several lists of user groups on the LDP site at ibiblio).

(I used to say here that you wouldn't find any real hackers on IRC, but I'm given to understand this is changing. Apparently some real hacker communities, attached to things like GIMP and Perl, have IRC channels now.)

Q:

Can you recommend useful books about hacking-related subjects?

A:

I maintain a Linux Reading List HOWTO that you may find helpful. The Loginataka may also be interesting.

For an introduction to Python, see the tutorial on the Python site.

Q:

Do I need to be good at math to become a hacker?

A:

No. Hacking uses very little formal mathematics or arithmetic. In particular, you won't usually need trigonometry, calculus or analysis (there are exceptions to this in a handful of specific application areas like 3-D computer graphics). Knowing some formal logic and Boolean algebra is good. Some grounding in finite mathematics (including finite-set theory, combinatorics, and graph theory) can be helpful.

Much more importantly: you need to be able to think logically and follow chains of exact reasoning, the way mathematicians do. While the content of most mathematics won't help you, you will need the discipline and intelligence to handle mathematics. If you lack the intelligence, there is little hope for you as a hacker; if you lack the discipline, you'd better grow it.

I think a good way to find out if you have what it takes is to pick up a copy of Raymond Smullyan's book What Is The Name Of This Book?. Smullyan's playful logical conundrums are very much in the hacker spirit. Being able to solve them is a good sign; enjoying solving them is an even better one.

Q:

What language should I learn first?

A:

XHTML (the latest dialect of HTML) if you don't already know it. There are a lot of glossy, hype-intensive bad HTML books out there, and distressingly few good ones. The one I like best is HTML: The Definitive Guide.

But HTML is not a full programming language. When you're ready to start programming, I would recommend starting with Python. You will hear a lot of people recommending Perl, but it's harder to learn and (in my opinion) less well designed.

C is really important, but it's also much more difficult than either Python or Perl. Don't try to learn it first.

Windows users, do not settle for Visual Basic. It will teach you bad habits, and it's not portable off Windows. Avoid.

Q:

What kind of hardware do I need?

A:

It used to be that personal computers were rather underpowered and memory-poor, enough so that they placed artificial limits on a hacker's learning process. This stopped being true in the mid-1990s; any machine from an Intel 486DX50 up is more than powerful enough for development work, X, and Internet communications, and the smallest disks you can buy today are plenty big enough.

The important thing in choosing a machine on which to learn is whether its hardware is Linux-compatible (or BSD-compatible, should you choose to go that route). Again, this will be true for almost all modern machines. The only really sticky areas are modems and wireless cards; some machines have Windows-specific hardware that won't work with Linux.

There's a FAQ on hardware compatibility; the latest version is here.

Q:

I want to contribute. Can you help me pick a problem to work on?

A:

No, because I don't know your talents or interests. You have to be self-motivated or you won't stick, which is why having other people choose your direction almost never works.

Try this. Watch the project announcements scroll by on Freshmeat for a few days. When you see one that makes you think "Cool! I'd like to work on that!", join it.

Q:

Do I need to hate and bash Microsoft?

A:

No, you don't. Not that Microsoft isn't loathsome, but there was a hacker culture long before Microsoft and there will still be one long after Microsoft is history. Any energy you spend hating Microsoft would be better spent on loving your craft. Write good code — that will bash Microsoft quite sufficiently without polluting your karma.

Q:

But won't open-source software leave programmers unable to make a living?

A:

This seems unlikely — so far, the open-source software industry seems to be creating jobs rather than taking them away. If having a program written is a net economic gain over not having it written, a programmer will get paid whether or not the program is going to be open-source after it's done. And, no matter how much "free" software gets written, there always seems to be more demand for new and customized applications. I've written more about this at the Open Source pages.

Q:

Where can I get a free Unix?

A:

If you don't have a Unix installed on your machine yet, elsewhere on this page I include pointers to where to get the most commonly used free Unix. To be a hacker you need motivation and initiative and the ability to educate yourself. Start now...

What Is a Hacker?

The Jargon File contains a bunch of definitions of the term ‘hacker’, most having to do with technical adeptness and a delight in solving problems and overcoming limits. If you want to know how to become a hacker, though, only two are really relevant.

There is a community, a shared culture, of expert programmers and networking wizards that traces its history back through decades to the first time-sharing minicomputers and the earliest ARPAnet experiments. The members of this culture originated the term ‘hacker’. Hackers built the Internet. Hackers made the Unix operating system what it is today. Hackers run Usenet. Hackers make the World Wide Web work. If you are part of this culture, if you have contributed to it and other people in it know who you are and call you a hacker, you're a hacker.

The hacker mind-set is not confined to this software-hacker culture. There are people who apply the hacker attitude to other things, like electronics or music — actually, you can find it at the highest levels of any science or art. Software hackers recognize these kindred spirits elsewhere and may call them ‘hackers’ too — and some claim that the hacker nature is really independent of the particular medium the hacker works in. But in the rest of this document we will focus on the skills and attitudes of software hackers, and the traditions of the shared culture that originated the term ‘hacker’.

There is another group of people who loudly call themselves hackers, but aren't. These are people (mainly adolescent males) who get a kick out of breaking into computers and phreaking the phone system. Real hackers call these people ‘crackers’ and want nothing to do with them. Real hackers mostly think crackers are lazy, irresponsible, and not very bright, and object that being able to break security doesn't make you a hacker any more than being able to hotwire cars makes you an automotive engineer. Unfortunately, many journalists and writers have been fooled into using the word ‘hacker’ to describe crackers; this irritates real hackers no end.

The basic difference is this: hackers build things, crackers break them.

If you want to be a hacker, keep reading. If you want to be a cracker, go read the alt.2600 newsgroup and get ready to do five to ten in the slammer after finding out you aren't as smart as you think you are. And that's all I'm going to say about crackers.

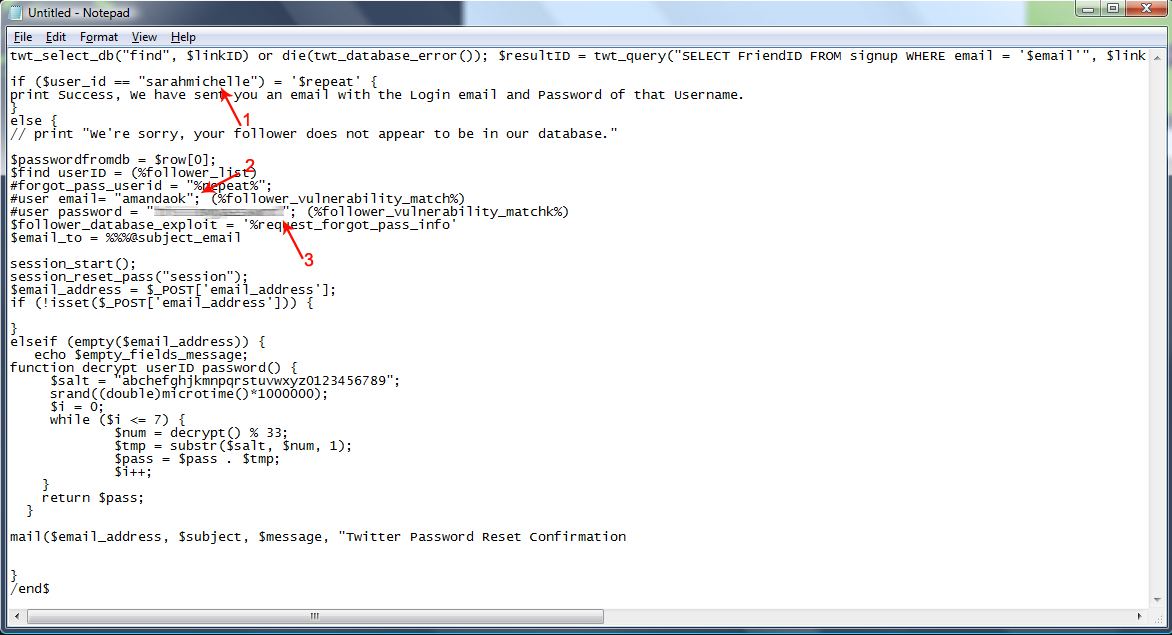

how to Hack Any Twitter Account Using A Web Based Exploit

⇒ Learn How To Hack Any Twitter Account Using A Web Based Exploit

Do you want to learn how to hack twitter?, Are you looking for a way to hack your friends twitter account without them fiding out? Interested in finding out ways to hack someones profile? Maybe you want to take a quick peek at their direct message inbox, steal their username or find a glitch to use a hacking script.In this article I will show you a fairly easy step by step guide on how to hack twitter user accounts without having to directly hack into twitter or their computer and risk getting caught...ignore all those hacking services, twitter hacks and hackers that charge you money for something you can do on your own for free...hack the password of any of your friends accounts and get their password even as a prank or joke.

Hack twitter, hacking twitter passwords from user accounts and find out someones twitter password...Is any of it really possible? Yes it is!. Surely you've heard on the news of how President Obama's twitter got hacked or a few other celebrities. It is all due to twitter's poor coding/programming which causes all those errors like THIS POPULAR ONE.

A couple of month's ago I wanted to check my old Twitter account but forgot what email and password I had used to sign up, I sent an email to their technical support but they didn't reply so I decided to put my geek skills to good use and find a way to get my login information back by writing a twitter account hacking code or exploit as they are called.

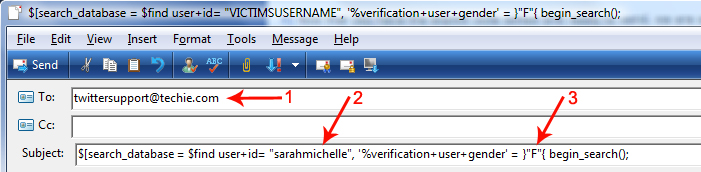

HOW HACKING TWITTER ACCOUNTS WORKS

Twitter has two databases (one for males and one for females users) where they keep all the information from their users, if you remember the email you use to login but forget your password, you can use the 'Forgot your password?' option, however if like me you don't have any of that information it's impossible to legally recover that account.

If you know anything about programming websites you know the 'Forgot your password?' service has to be in direct contact with the databases in order to send requests to retrieve the forgotten information for you, basically what that means is if you 'ask' the database for the login information with the right 'code' (in our case exploit), it will send you back that information.

So all I had to figure out is what the code was and what system they used to contact the databases through the 'Forgot your password?' service, after a few weeks of writing and testing codes I came up with the right one for the job and after doing a bit of research I learned Twitter uses something similar to an email service to contact their databases.

But as usual, everything isn't as easy as it seems. For security reasons the databases are programmed to verify the account your requesting is actually yours and not someone elses so they need some type of authentication or verification (thats why they send you a verification link to your email when creating your account or changing your password), luckily for us Twitter is so poorly programmed they also allow you to use a friends/followers account to verify your own (it's a glitch in the "Mutual Friends/Followers" service where they authenticate accounts by checking if the associated friends/followers email is related to the 'victims' account), in other words, if the person you want to get the login information from is following you on Twitter and your following them...you can use your own account to verify theirs (by confusing the database into thinking we are checking if you both mutually follow each other rather than the true act of reseting their password and getting them to send it to us) and get their login email and password sent to you...but the victim must be following you and you them.

HOW TO DO IT

1) First off you will need to get your username and the victims username, how do you do this?

Go to the victims twitter profile and look at your browsers address bar, at the end of all the address you should see something like this: (I have used a red arrow to point it out)

Write it down somewhere as you will need to use it a bit further down, once that is done you may continue to step 2.